Ghostly fishes and parasitic genomes

- Kevin Thiele

- Apr 7, 2019

- 4 min read

Here's a riddle. Can you be a parent to your birth children, but not be a grandparent to theirs? Some very peculiar fishes in the rivers and streams of the Murray-Darling Basin and adjacent catchments do exactly this. Like the riddle, this story will probably do your head in.

We usually think of extinction of a species as the end of its road. Like the dodo, thylacine or woolly mammoth, extinct species are gone for good (though some are not forgotten, by taxonomists at least).

But - there are a few little-known exceptions, 'ghost' or 'semi-living' species that aren't quite gone, but live on in a very peculiar way. One well-studied example is in the Australian carp-gudgeon fish genus Hypseleotris, one species of which is living and apparently thriving over a range of thousands of kilometres of river, despite being virtually extinct.

The genus Hypseleotris comprises around 16 named species, eight of which occur in Australia. One colourful species, the empire gudgeon (H. compressa) from eastern Australia and Papua New Guinea, is quite popular in aquaria.

As well as these named species, several carp-gudgeons in the Murray-Darling, Bulloo and Cooper Creek catchments of eastern and central Australia have not yet been named, because they have long been regarded as taxonomically tricky: they are not easy to tell apart, and readily hybridise. And this is where the story gets complicated.

Hybridisation in nature isn't all that unusual, especially in some groups like plants. A hybrid receives a set of chromosomes from each parent. If the hybrid is fertile, it can usually successfully mate either with other hybrids or with either parent (a back-cross). During these matings, the genomes from the two parental species gradually merge through genetic recombination. The outcome in some cases may be that the two parent species gradually merge through their hybrids and become one species; in others the parent species remain distinct but gain new genetic material from the other.

But that's not the only outcome. In a small number of cases, the genomes of the two parent species don't merge but remain quite distinct through the generations. If this happens, one of the parent species could become extinct as a species, but would 'live on' through its hybrids.

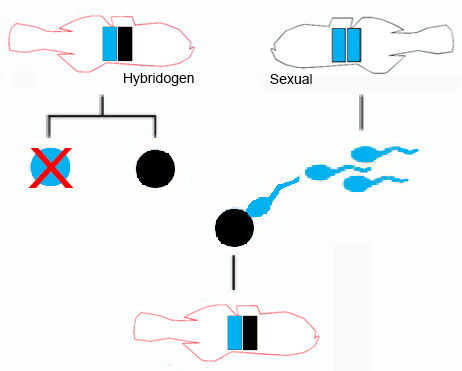

And this is exactly what happens in the Australian carp-gudgeons. Three currently un-named species are involved, called HA, HB and HX (the H stands for Hypseleotris). HA and HB are both widespread, as are the hybrids HAxHB. But the HAxHB hybrids are hemiclones - when they mate with one of the sexual species HA or HB, the mating will always produce another HAxHB hemiclone. This is because half the hybrid’s genome is passed on clonally to the offspring without any recombination, while the other genome, inherited from the sexual individual, is replaced every generation.

And that's the answer to the riddle: the sexual parent is a parent to its offspring, but will not be the grandparent to its offspring's offspring (unless it mates again with its own hybrid offspring). The following diagram might make it more clear.

So that accounts for the HA and HB 'normal' carp-gudgeon species and their HAxHB hemiclones. But initial studies in the early 2000s also found two other widespread hybrid genotypes, called HAxHX and HBxHX, both of which again were hemiclones. The HX genome was only ever found in the hemiclonal hybrids, leading researchers at that time to conclude that the HX sexual species was probably extinct, but lived on as a 'ghost' species, reproducing 'parasitically' through matings between the hemiclones and the HA and HB sexual species. This could make a good plot for a zombie movie.

More recently, though, a tiny population of pure HX sexual individuals has been discovered in a few tributaries of the Lachlan River near Gunning, north of Canberra. (When reported in the Canberra Times, one of the researchers was perhaps less than flattering about Gunning when he was quoted as saying 'Totally wasn't expecting to find it, especially not in Gunning of all places'.)

Hemiclones are not the only way that a species can remain 'alive' even when it becomes extinct. Other mechanisms such as allopolyploidy can have the same effect, especially in plants. But hemiclonality is perhaps one of the more complex and interesting variants on the 'normal' pattern of sexual reproduction. The exact mechanism by which the hemiclones always produce identical offspring without recombination is still unknown, and the subject of further study.

One of the more bizarre but encouraging consequences of hemiclonality is that, for species that can make a hemiclonal hybrid lineage (and unlike the dodo and thylacine), extinction may not be forever. There may be mechanisms by which an extinct species that lives on as a 'ghost' in its hemiclones could be reborn, perhaps by some unusual types of matings between two hemiclones. In the case of the HX carp-gudgeons found near Gunning, careful analysis showed that this had not happened - the populations in fact represented the 'original' rather than a 'reborn' HX.

Another consequence is that conservation of these remarkable fishes, especially the very restricted HX sexual species near Gunning, is critically important. The Murray-Darling system is badly stressed, as shown by the mass fish-kills in the lower reaches of the Darling. Further fish-kills and environmental degradation through land clearing, drought and climate change could mean the loss not only of a river and its ecosystems but of a remarkable and fascinating story, and an insight into an extraordinary 'tributary' of evolution.

To understand more about the remarkable 'ghost' carp-gudgeons, try the following:

Thanks to Michael Hammer, one of the researchers involved in studies of the Murray-Darling carp-gudgeons and currently based at the Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory, for relating this story. If any residents of Gunning read this story, Michael was not the one who was rude about your town.

Comments